For most of my life, I aspired to own my own home — a little house with a yard, maybe a garden, maybe even a few trees. In Los Angeles, on a documentary filmmaker’s income, that kind of dream usually puts you fifty miles east of the city and certainly nowhere near the ocean. For years, I tried to figure out how to put my love for nature and the coast first and still make it work. Eventually, I found it in a 670-square-foot single-wide at the Tahitian Terrace Mobile Home Park.

When most people think of the Pacific Palisades, they imagine an affluent pocket of the city where celebrities hide behind hedges and gated driveways. What’s less known is that nearly 30% of the Palisades was made up of multi-unit housing — condos, townhouses, apartments and mobile homes — the only housing that was actually accessible to low and middle-income residents. When I bought my mobile home on Kiki Place, it felt like I’d won the lottery: a place by the beach, finally within reach. What I didn’t fully understand then was what it truly meant to own a mobile home — the structure itself, but not the land beneath it — until the Palisades Fire destroyed it.

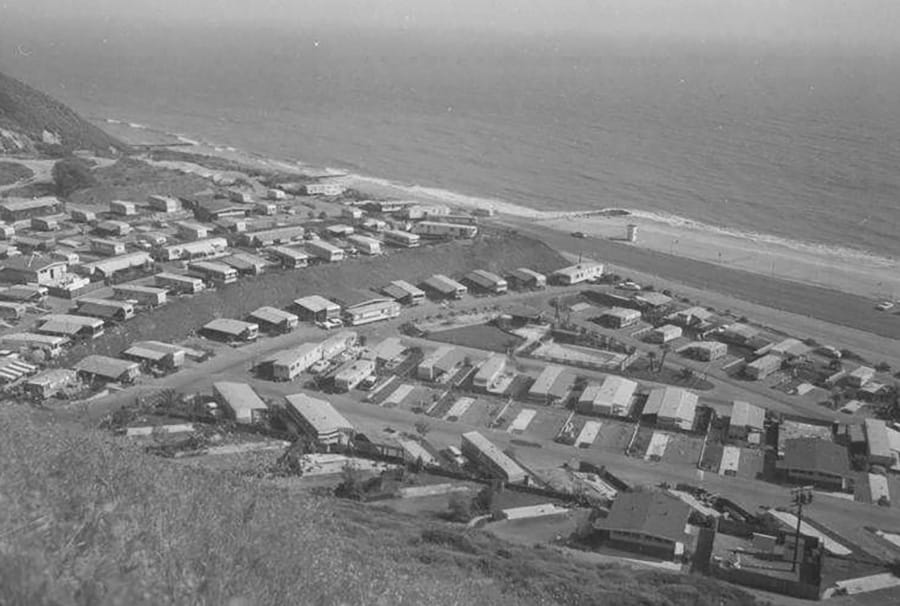

Tahitian Terrace was established in 1962 as a senior rental park, tucked into a terraced hillside overlooking Will Rogers State Beach. Over time, it evolved into a diverse, all-ages community of more than 150 homes that were family-owned, long-held, and deeply rooted. The park drew people who liked a bohemian lifestyle with practical sensibilities: teachers, artists, public workers, firefighters, and people who had spent decades in the entertainment industry. It wasn’t flashy. It was down to earth, and I truly felt like I had found home.

I had bicycled past the mobile home parks along the PCH for years before one day deciding to stop and take a closer look. That was the moment I knew I had found something special. As I got to know my neighbors, I fell for the spirit of the place — the eclectic rows of homes, each personalized with surfboards, seashells, wind chimes and hand-built decks. It was lived-in and real.

My home backed up to a hiking trail and offered a peekaboo view of the ocean. Neighbors told me stories about the woman who lived there before me, who decorated the yard with little gnomes. The quirkiness fit my vibe. We all seemed to understand something unspoken: we had figured out how to live a dream lifestyle by embracing, rather than resisting, the stigma of living in a mobile home park. We knew what we had and it felt priceless, until January 7th when the fire destroyed our community.

What took me more than a year to figure out and find was gone overnight. I had just closed escrow the day before the fire — proof, if nothing else, of how fragile “ownership” can be. In the days that followed, I found myself buried in disaster recovery paperwork, fighting for rights I didn’t even know I needed. This is the part of mobile home living few people talk about: ownership stops at the walls. Insurance rarely reflects reality and payouts are based on the replacement value of a single-wide mobile home — not the views, the location, or the zip code where you pay taxes. And after a fire, the decision about whether you can return no longer rests with the people who lived there, but the ownership group of the land.

This has been the hardest part to reconcile — not just the loss, but the silence. One hundred and fifty-eight households were displaced from Tahitian Terrace, and in the year following the fire, residents have received little to no meaningful communication from the park’s ownership group about rebuilding, timelines, or whether returning home will even be an option.

I was quickly educated on the fact that mobile home parks occupy a strange middle ground. They’re often described as affordable housing, yet treated like private real estate when disaster strikes. Residents invest their life savings into homes they cannot easily move, while the land beneath them remains a commodity. When a fire destroys the structures, the land remains — and with it, the opportunity for redevelopment. They are vulnerable by design.

In places like the Pacific Palisades, and increasingly everywhere else, where land values soar and coastal access grows increasingly exclusive, disaster does not hit evenly. It exposes long-standing fault lines around class, age, housing type, and who is deemed worth rebuilding for. Tahitian Terrace was home to people who had already figured out how to live smaller, slower, and closer to the land. Many cannot simply relocate again. For some residents, this was the last home they expected to own.

What happens to Tahitian Terrace will quietly signal how Los Angeles intends to rebuild after climate disaster, and whether recovery includes working-class communities or whether fire becomes another mechanism for erasure. I am still standing in the aftermath, learning how land use, insurance, and recovery policies show up in ordinary days and unanswered questions. This is not simply a story about losing a home, but about the fragile line between rebuilding a community and watching it disappear.

Disclaimer: The content shared in our blog is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal, medical, or financial advice. Please consult with a qualified professional for guidance specific to your situation.